Our guests are artist Grayson Earle, the collaborative team who made White Collar Crime Risk Zones (Brian Clifton, Francis Tseng, Sam Lavigne), and artist and organizer ann haeyoung.

In the Software for Artists Book: Building Better Realities, Grayson says:

[I’m] not so shy about the distinctions, like, “Is it art? Is it activism?” I think these things are kind of funny constructions. For me it’s never a question of, “Is it art?” But, what does it afford us to call something art that we might be more comfortable calling activism?

Grayson has been building the Counter-Productivity Suite, a series of tools for workers in crisis. These tools are meant to aid striking workers and to connect their plight to historical labor history.

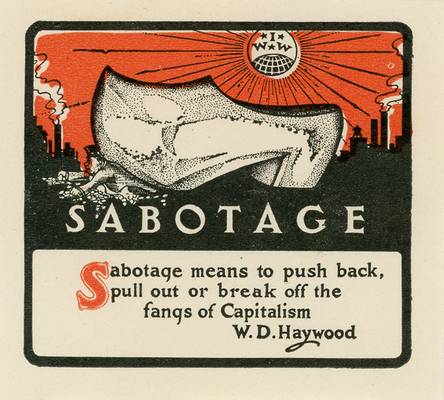

Grayson points out that the root of the word sabotage is an old French word for shoe forms: sabot. He describes how peasants arrived in Industrial Paris to work in factories and experienced unfair labor conditions. The story goes that they resorted to disrupting the means of production, at times by throwing their wooden shoes into the machinery. In one of his current tools, he considers what form this shoe could take in the current era.

We also speak with the team behind White Collar Crime Risk Zones, Brian Clifton, Francis Tseng and Sam Lavigne. White Collar Crime Risk Zones uses machine learning to predict where financial crimes are mostly likely to occur across the US. It is a commentary on predictive policing and algorithmic bias.

Sam believes art has the power to clarify, to make clear issues of inequity. Francis holds out hope that artists building tools and technology can subvert power, though he warns us we should be ready to abandon our tools at any time. And Brian identifies as a former artist and current data scientist, someone that knows how data works and can wield and deploy data sets.

ann haeyoung takes a different approach to considering art and activism. She creates sculpture and performance work, which she considers to be a separate process from her work as an activist and organizer and tech worker. She brings this past and current experience to bear as her work spotlights issues of identity and inequity arising from corporatized technology.

Grayson Earle is a new media artist and educator. He has worked as a Visiting Professor at Oberlin College and the New York City College of Technology, and a part-time lecturer at Parsons and Eugene Lang at the New School. He is the co-creator of Bail Bloc (along with Sam Lavigne and Francis Tseng) and a member of The Illuminator art collective. He is currently based in Stuttgart, Germany as a fellow at Akademie Schloss Solitude.

Brian Clifton is a data scientist who is critical of how the field is used to launder biases and systematize oppression. His work employs machine learning, algorithms, automation, and data to expose the anti-human logic of technology and power.

Francis Tseng is a researcher who designs and implements simulations & games, designs and implements procedural & AI systems, develops software & web applications, and builds software tools.

Sam Lavigne is an artist and educator whose work deals with data, surveillance, cops, natural language processing, and automation.

ann haeyoung is an artist currently based in LA. She uses video and sculpture to examine questions around technology, identity, and labor.

Our audio production is by Mimi Charles and Max Ludlow. Episode coordination and web design by Caleb Stone. This episode was supported by Purchase College.

Our music in this episode includes Idiophone by Bio Unit, Further Discovery by Blear Moon, and Crystals by Xilo-Zyko.

This episode is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Lee Tusman:

You’re listening to Artists and Hackers, a show dedicated to the community building and using new digital tools of creation. We talk with programmers, artists, poets, musicians, bot makers, educators and designers. We’re looking at the current palette of art making tools online, and take a critical eye to the history of technology and the internet. We’re interested in where we’ve been and speculative ideas on the future.

In 2021, what it means to be an artist working with technology is wide open, and we’re here to explore it in detail, especially looking at issues of equity and justice. In today’s episode, we’re talking about art and activism, tool building and technology. This episode of Artists and Hackers is supported by Purchase College. I’m joined in the virtual studio today with our audio producer Mimi Charles and coordinator, Caleb Stone. In our first episode, we talked with artists that build languages as tools and artworks. And in this episode, we’re talking to artists that make tools as artworks and activism.

Caleb Stone:

I think what makes this episode specific is it’s kind of about the interaction between active tools for activism and art as symbolic activism, like that is kind of the thing that we’re working with here. We have people that are building actual tools that do actual things, then we have people that are building tools that do something that’s kind of symbolic, and then we have people that have completely separated those two parts of their practice.

Lee:

I think that’s a really good point. And I think what you’ll hear is there’s these really different approaches and different ways of thinking of the power of art or the power of technology, to even comment on social justice as well.

Caleb:

Right, so I mean if we’re talking about some sort of spectrum between art that is activism, art that is symbolic activism, and then art that is symbolic, related to activism. Grayson’s really falls towards the side of being actual tools that protesters and activists can use.

Grayson Earle:

My name is Grayson Earle and I have been bouncing around as a professor visiting adjunct and otherwise, and I’m hopefully headed to Academy Schloss Solitude in the fall to be a research fellow for nine months. So just sort of a teacher, artists, activists, something, something in there.

Lee:

How did you get into making art? My understanding is that you studied film first and then moved into art and started integrating technology. Do you mind saying what led you to becoming an artist?

Grayson:

Yeah, I mean, it’s kind of funny, I wonder how many new media people feel that they have a bit of a challenging relationship with the the title of artist. But yeah, I mean, I was studying to be a filmmaker. I wanted to be like the next Alphonso Cuaron or something and make like science fiction, dystopian films, and then kind of ended up through an advisor in undergrad was like introduced to Hunter College’s IMA program. And I started to get like more interested in documentary filmmaking. And they have like this sort of creative nonfiction MFA that’s basically like a Marxist-feminist documentary film program. And then there was kind of discovering that I wasn’t a filmmaker, because I wasn’t any good at it. And I didn’t have the personality I think that you need to be able to lead essentially. And so luckily, my advisor at Hunter Ricardo Miranda is a new media artist. And he introduced me to Arduino and Processing and all of this stuff. And so ever since then, it’s been like, yeah, that’s been it for me, you know. And I have a bit of a background in programming. So it was easy to pick up, I think, a lot of this stuff. But it’s Yeah, it’s been like the last, basically, since I’ve been in New York, which is like 10 years now, sort of practicing this, this sort of art.

Lee:

And how did you get involved in making this kind of work of making art as activism?

Grayson:

Well, activism has always been a part of my life, much like programming has always been a part of my life. Although, you know, I wasn’t really practicing neither of those things super intensely for a while. And I think activism really ramped up for me when I moved to New York, because shortly after Occupy Wall Street came about. And I was actually there on the first day, I had seen it as you know, the first incarnation, which was the image in Adbusters. And just sort of showed up, and didn’t realize it was gonna turn into this, like worldwide event, you know, but that that got me introduced to a lot of interesting people and ideas. And you know, it’s happening alongside grad school. And I ended up basically, in this crew, the Illuminator.

Caleb:

Hey Mimi, didn’t you actually see the Illuminator in action in the city?

Mimi Charles:

Yeah, actually I did. I was in the car with my mom. And we were driving on the Brooklyn Queens Expressway. And, as we were driving by there were like these words on a building. And when I looked at it, I saw it was like, “I can’t breathe.” And it was like George Floyd’s last words before he died. So I didn’t really even know who put it there, or how it got there. But it was like really emotional seeing it, because it just showed like, how impactful his death was, and how impactful it still is, because we’re interviewing Grayson about it, but I had no idea he was the person that was like, also behind creating that moment and experience for me in the car.

Grayson:

The Illuminator is a video guerrilla projection collective. But in material terms, we are a group of people with a van and a very powerful projector. So you know, like a typical classroom projector is something like 2000 lumens, and we have a 12,000 lumen projector. And we tend to use it to project huge protest signs on to the architecture of New York City and actually other places around the world, but typically New York City. And yeah, it basically works as a kind of like, in a way that most people don’t have the ability to buy a billboard space and stuff like that in a city, it kind of works on behalf of the 99% to help us kind of reclaim the visual environment with our own messaging. And by our own I mean, the working class and you know, everyone who doesn’t have that kind of money.

Lee:

Do you ever worry about getting arrested?

Grayson:

Well, with the illuminator, we do think about getting arrested. And you know what the best way to protect ourselves in those situations is, I mean, the first thing that’s really important to say, in these sorts of discussions is that like privilege operates in all these situations, right? So like, when we’re projecting, I’m a white guy. And so it makes a lot more sense for me to interface with the cops, because there’s less of a chance of them, like being violent against me just like statistically, than some of my other collective mates. And so, you know, it makes sense to, like, plan that out. And we often do, we’re like, okay, you know, it might not be me, but someone in the group is going to be like, on police duty.

Lee:

You’ve cited previously the artist Ricardo Dominguez and his project FloodNet, what was that? And how did it influence your approach to making art?

Grayson:

Yeah, I mean, the Electronic Disturbance Theater and Ricardo Dominguez, they created FloodNet, which is some software that people downloaded. They did performance in 1998, where they asked people to download the software. And everyone that downloaded it could click, you know, start on their computer. And they all send these low level network requests to the World Economic Forum. And by low level requests, I just mean, like a ping a simple like, hello. So hundreds of thousands of these Hello messages going to the World Economic Forum’s website at once, and it took it offline. And so everyone, you know, got a chance to partake in this thing that was only possible with the collective. And so with Ricardo Dominguez, his project is interesting because he is very obviously an artist. He, you know, like, takes that label. He’s an artist at UC San Diego as a faculty member and so like, he can kind of like claim that you know. He did that. On the one hand, you know, he called it performance art. And so therefore, it’s like in this sort of space, where it’s okay to maybe do things you’re not normally supposed to do because it’s art. And then also he called it a virtual sit in, virtual sit in which you know, likens it to a lot of the civil disobedience that was going on in the 60s. And so that’s really cool because it gives it, it grants it historical meaning. So it connects it to this, you know, practice of protests. And then it also, like, kind of makes people think about the practice of DDoS or hacking differently. Like it kind of includes it into political activism and creative practice.

Lee:

Yeah, that makes me think about your collaborative project Bail Bloc, which is described as a cryptocurrency scheme against bail. I’m wondering how did that come to fruition?

Grayson:

So with Bail Bloc we’re mining Monero. And so everyone doing this together with Bail Bloc, we take all of those rewards, sell them Monero that we’ve generated for US dollars, and then use that money to bail people out of jail. Previously, people who are detained in New York City, and now we’re working with the Immigrant Bail Fund in Connecticut for people who have been detained by ICE.

Lee:

Wow. And I know more recently, you’ve been working on speculative tools for workplace protest.

Grayson:

Yeah, I’m working on among other things, a shoe that sabotages the workplace. I chose the shoe and the word sabotage because they’re actually intimately related in the etymology of sabotage, which apparently, I found out through my research. The word sabotage comes from the French root sabeau, which is like a workers shoe. And they would throw their shoes into the delicate machinery in like the early 1900s, or late 1800s. To stop them from working, when their bosses wouldn’t pay them or whatever, they would take their shoes off and throw it into the machines to stop them. And so the project that I’m currently involved in is to build this shoe that shuts down Wi Fi networks in an area. And this is kind of a response to like the new the modern workplace, which is, you know, in some ways is a misnomer, because there are so many workplaces. But when I think about a lot of the recent unionization efforts, like at Vice, or Kickstarter was actually just successfully unionized. Their offices are just these big open rooms with Wi Fi. And so if you were to shut that down, or give them the ability to shut that down, that gives them significant leverage. Because, you know, it’s like work is over for the day if no one can get on the Wi Fi network. And so that’s where that idea came from. And then you know, it’s an issue because then for one to connect it to this idea of like the wooden shoe and the, you know, early French industrial era, but also like, it’s it’s covert, you can walk through the office and no one’s gonna know that you’re shutting down the Wi Fi, which is kind of cool.

Lee:

Well, thanks, Grayson.

Caleb Stone:

Something that’s really beautiful about Grayson’s work that I think a lot of artists have struggled trying to reckon with is making their useful tools artistic and poetic. Grayson does a really great job of that, like all of his tools, and all of his objects that he creates are really rooted in histories of resistance and activism. I love when he talks about the history of the word sabotage and how he used that as inspiration for his shoe.

Mimi Charles:

Yeah, completely.

Lee:

I love that the idea of rooting this very contemporary subversive art practice in the history of labor activism. And maybe now’s a good time to introduce our collaborative group, Brian Clifton, Francis Tseng and Sam Lavigne. Like Grayson, they’re also using contemporary technology. They work with machine learning to tackle entrenched structural problems like inequality and systemic racism. And I’ll let them introduce themselves.

Brian Clifton: I’m Brian Clifton. So when someone asked me, What do I do, I say, I’m a data scientist. And I specifically also say that I do not make art anymore. Because that was a hat that I used to wear. And I think it’s more interesting to like, think about the things that I make is not art. So if someone asked me if I’m an artist, I usually decline.

Francis Tseng:

I’m Francis Tseng. What what label I apply to myself like this is something I’ve always struggled with. I think now I use the term researcher just because it’s my job title. But yeah, usually some combination of researcher and software developer, something like that.

Sam Lavigne:

I’m Sam Lavigne. I usually say I’m an artist and a teacher. But then I don’t love saying that I’m an artist. But I just do it anyway. I don’t know. I mean, I don’t sell art. So you know, I mean, sometimes I get a little bit of money here and there to make something. But I’m not like, I’m not a commercial artist. And then, if I have to say anything more specific, I usually clam up. But sometimes I have been saying that I’m a conceptual internet artist. But that makes me like, cringe super hard. So I try not to say too much. Yes.

Lee: Can you describe what is White Collar Crime Zones, and where the project idea grew from?

Sam Lavigne:

I mean, I definitely remember Brian sort of initiating the idea of doing some kind of predictive policing, some kind of response to predictive policing. And I guess we should say what predictive policing is also, right? So predictive policing is just a policing methodology, where you create a system to try to predict where and when crime is going to happen, based on historical data about where and when crime has already occurred. So you gather all this data about where and what crime has occurred, and then you build a system in putting that data to try to predict where things are going to happen in the future. And there’s a number of companies that make systems like this, and there’s a number of police departments all across the world, that that use these systems. So, like, what’s running? You know, what’s wrong with this? Right? Why Why would this be a problem is probably like the next question. Right? And it, you know, there’s a pretty simple answer, which is, which is just that the data collected by these police departments, you know, it comes from what we what really is, you know, historically, systemically racist police departments. So predictive policing applications tend to create this like, feedback loop, right, where they, they reinforce the idea that particular groups of people need to be policed, and they lead to situations where communities that are already over policed, become even more over policed,

Brian Clifton:

Right, there’s no such thing as crime data like that, that doesn’t exist. They’re only arrest data, or like actions that police officers, you know, recordings of, like, interactions with police officers and citizens. And so that’s, that’s what that data is there’s. So these systems are not based on crime. They’re based on interactions of police in the community.

Sam Lavigne:

We did some research about what predictive policing apps do. And then we tried to build our own as faithfully as we could, they just like changed with the data set was from quote unquote, street crime to, to white collar crime. And Francis was like, really largely responsible for that component that like machine learning component. Because Francis is an incredible machine learning researcher, and practitioner. So he figured out like a really, like elegant and simple way that was faithful to take the data that we were able to find and to and to make a predictive system using it.

Francis Tseng:

If I recall correctly, we found a presentation by HunchLab, which is one of the major vendors of, of predictive policing systems. And that presentation, I think, outlined their model in enough detail that we can basically replicate it. And yeah, and literally just change the data set.

Brian Clifton:

Yeah, one of the fun things about I wasn’t I’m not sure if it was exactly contrived, who did this but like a lot of the predictive policing algorithms used a variety of other types of data to improve the predictive power of their their models. And, and some of them are just absolutely wild, like moon cycles or proximity to like bars or, or proximity to public transport. And so we we included some of that, you know, like, performance boosting data into our system as well. I don’t know Francis, do you remember any of the other data sources that

Francis Tseng:

I definitely remember the moon one. I can’t. That was the one that seemed the most absurd,

Lee:

As in, when you’re saying the moon one… some of the predictive policing. use that as part of their algorithm. They would use this cycle of the moon to help inform their predictive policing algorithms?

Francis Tseng:

Yeah, I think that justification was something like if, if there’s a fuller moon, there’s more light out. So people are more likely to be outside committing crimes or something like that.

Lee:

That’s bizarre. And it points out the absurdities in these models. And your project has been really effective I think overall at pointing out the biases and problems of so called neutral algorithms. I’m curious to hear now that it’s been a while since you created this project, if you think these kinds of works can be effective at dismantling structures of oppression.

Brian Clifton:

One of the reasons why I can justify myself working in data science is to learn the tools of data science in order to subvert the problematic parts of data science, or kind of run counter to the people who, whose ethics or politics i disagree with. And still have, you know, and do it right, you know, like, not do it because I wanted to learn it both because it’s like, the kind of thorough and proper way to do it.

Sam Lavigne:

I’m not sure if it’s possible to do that. You know, I mean, not not, I might not actually respond to what you’re saying, Brian, just to sort of more generally speaking, you know, like, like, I’m not sure how possible that is. One thing that I do think that technique really allows you to do is produce some level of clarity. Right? About what what those tools are actually doing. And, and I think that’s really important because they frequently those tools, especially technical tools, are so surrounded by their hype, their hype men, you know, that it can be really hard to understand what they’re actually doing, what their goals are, and, and and who they’re really serving, right. And so when you attempt to, like investigate a tool by like, say, again, like, let’s talk about predictive policing, what are you talking about? That is like, my reverse engineering it, you can, you can bring a lot of clarity about what it’s actually doing to a group of people who might not be aware of it. Right. And that, to me, at least, is an important function. I’d like to think that you could, you can, you can like subvert tools and then enact some kind of, like power shift, because of that. Um, ah, but I think the jury’s still out.

Francis Tseng:

Yeah, I go, I go back and forth. This whole masters tools question is something that I also think a lot about, and I go back and forth on a lot. And I think where I’m at with it now is maybe also this kind of “Yes,” with a lot of caveats and conditions, and maybe better to say, those tools can help but you should be ready to abandon them at any moment. And you shouldn’t trust them. Yeah, I think that’s kind of where I am right now. With that.

Lee:

Well, thank you so much for speaking with me today. Thanks for having us. And listening back to the section I’m thinking about how Sam believes art has the power to clarify. To make clear issues of inequity. Francis holds out hope that artists, building tools and technology can subvert power, though he warns us we should be ready to abandon our tools at any moment. And Brian identifies as a former artist, and now current data scientist, someone that knows how data works, and can wield and deploy datasets. So I was also curious to speak to an artist that’s not creating web based interactive work but whose work seems clearly situated in Fine Art Media. I talked with anne haeyoung, an LA based artist that uses video and sculpture to examine questions around technology, identity, and labor. Like many of the people I’ve spoken with, anne wears many hats,

anne haeyoung:

I’m anne haeyoung. I have been describing myself as an artist, tech worker and an organizer.

Lee:

I think I’m curious how you’d say your art practice relates to your organizing work, for example.

anne haeyoung:

I have been thinking of them as somewhat separate. I think a lot of artists kind of wonder what is what is art activism and does that mean I’m making posters or I’m making a video which can then you know, make somebody show up to a protest or something like that, and I feel like that is less what it has been for me at least up until now. The art that I’ve been making I feel like is a way for me to reflect on and understand the organizing work, the tech work that I’m doing. And so I feel like art has been a way for me to, to kind of explore the critical side of technology, which then feeds back into my activism. But it’s not necessarily directly like the art I’m making is supposed to be, like, leading to this type of change. I think the way that they have intersected more directly in that way is when I have opportunities like this, or other opportunities to speak to people, whether it’s like giving a talk or doing a workshop or whatever. And in those more in those settings, where you can kind of, you know, talk to people one on one after a talk or during a workshop or whatever, then really get people to think differently about work and our relationship to technology. And to think more critically about technology. I feel like those opportunities have been kind of been like the way that my art has been more directly linked to my activism.

Lee:

I’m looking at documentation of your blood batteries series, and I’m reminded of like a lemon or potato clock. But I’m also kind of very, maybe viscerally affected by the appearance of these batteries made out of blood with like electrodes in them. Can you can you say more about that project?

anne haeyoung:

Yeah, so that was the inspiration for that was the Korean word for mixed races which translates to mixed blood. And there’s also this idea in Korean culture of the one blood people. And so thinking about how we use blood as a synonym for kinship, but a lot of the times when we are, just because we might share blood with somebody, that doesn’t necessarily mean that that we share any sort of meaningful relationship with them. So I guess that’s kind of what I meant by that question is like, what other ways do we create relationships? And, and, you know, are there more useful ways of defining ourselves and how we relate to one another. So I also think a lot about the tech industry. As I mentioned, I’m a tech worker, or I was a tech worker. And so thinking a lot about how, you know, when we are putting our identity into technology, it is these large tech companies and these kind of tech giants, people like Elon Musk, who are doing a lot of that defining of how they think about identity and how they want that to be put into the technology that they create, or facilitate the creation of and so putting this the the large blood battery that I did was a performance in front of the Tesla Giga factory out in sparks, Nevada. That was the first Tesla battery factory. It was, or maybe still is the largest square footage building in the world. So it’s like this enormous factory, I think it’s kind of, it’s like testament, or that’s not the right word. I feel like it’s Elon Musk, putting all of his ideas about technology into a physical form. So it seemed like an appropriate place to have that conversation about like, what technology is, what, how, you know, we create technology and how, what that means.

Lee:

So hearing about your work as an artist, and about your experience as a tech worker, as well, as an activist, I’m curious to hear what you think the role of artists and hackers are to work toward issues of justice and equity.

anne haeyoung:

I guess as a more a roundabout way to answer this as like, in the tech world for like, you know, part of what I was doing is organizing with other white collar tech workers and, and, but there’s only so much you can change within the institution. And I think the art world is the same that it’s the way that it’s organized and the way that people make money as artists purely as artists, if you’re selling an art gallery, or getting grants from, you know, foundations that might have questionable origins of where their money is coming from, like, there’s only so much you can do, like we all do exist within this broader system. So I think there are a lot of artists that are finding ways outside that like I think specifically outside like the gallery system and that way of making money but and I think artists do, I think what I love so much about art is that artists give me a lot of hope of of creating alternative systems and whether it’s like of how to exchange work or how to educate one another, and how to support one another. So I think that in that sense, like yes, maybe that there there is ways to create art and to inspire others to show them like here’s a way that we are like in community with one another outside of capitalism. But there’s also the reality that like, we do need to somehow make money. And so you do need to plug into the system somehow for that.

Lee:

That is true. You’re right. anne thanks for speaking with me today.

I guess we keep coming back to this issue of art and its ability to make social change. And how can it make social change? can it make social change? Or can it break down oppression or is it just a tool of structural violence and oppression? Have your views based off of you know, speaking to these different people, have your views on this change at all?

Caleb Stone:

Well, I guess this is what gets interesting when we’re talking about art as tools. Because I think my immediate response to can art make meaningful social change is not necessarily that I think there are certain instances where it provides a lot of visibility to certain issues. But at the end of the day, I’m definitely a person that feels that things that perform actual functions are a lot more useful. And so when we’re getting into this weird gray area, where we’re talking about art pieces that do something that is kind of symbolic, and also kind of useful, it gets a bit tricky to answer this question. But at the end of the day, I do think that using technology and using these systems that have been historically used for oppression, against themselves, and for building tools for protest, and social activism, is a useful endeavor, and can actually provide social change, whether it will inevitably bring down the man is up for debate, but I do think that they’re particularly more useful than making a symbolic work of art.

Mimi Charles:

Yeah, definitely. And I think as well, the thing about art when it comes to creating social change, and, you know, striving for equality is that sometimes it can even just motivate people to push for, for those things, especially like for me, like being a black woman, like, it’s very tiring dealing with racism every day. So I think when there’s art that kind of motivates you to either do something that’s legislative or get involved in a way that isn’t artistic, even if it’s through coding programs that can help people get money for bail, all of that. I feel like it’s still connected in a way. So I don’t think one has more importance than the other. I feel like, in a way, it always can result in a collaborative process and effort that reaches an end goal.

Lee:

Yeah, thank you. One of my goals for the episode had been to explore the many ways that artists and hackers choose to present and act on their own political ideals. And like this can take the form of activist artworks. It can function symbolically, be poetic, it could take the form of direct action where, you know, using one’s own power to reveal alternatives to systemic societal problems and issues of race and class. And I’m also thinking about how one can choose a constellation of approaches and actions creating artwork that poetically speaks to issues of inequity and a work outside of one’s own artistic practice on activist goals. Our guests today reflect the range of these approaches, and we’ll explore more of these in future episodes.

That’s our show today. You’ve been listening to Artists and Hackers. I’m your host Lee Tusman.

Audio production by Mimi Charles and Max Ludlow. Web design and coordination by Caleb Stone. Thank you to Mimi and Caleb for Joining me in the studio.

Our music today was videophone by Bio unit, Further discovery by Blair Moon, and this is the track Crystals by Xylo-Ziko. This episode was supported by Purchase College. Thank you to our guests on this episode Grayson Earl, Brian Clifton, Frances Tseng, Sam Lavigne and Anne Haeyoung. You can find episode information and links to all of our guests on our website, artists and hackers.org You can find us on Instagram at artistsandhackers and on Twitter as artistshacking. If you liked our show, please let a friend know and we’d love to hear your feedback on the episode. You can email us at hello at artists and hackers.org thanks so much for listening.